Black and white images of violent destruction expose a staggering disregard for human life, and although discomfort begs viewers to turn their heads, the TU McFarlin Library Department of Special Collections and University Archives encourages Tulsans to ignore that impulse. For the second time in TU history, special collections will feature a special public exhibit, “Images from the Burning; the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in Special Collections.”.

From March 23 – June 1, 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., visitors can explore this rarely seen collection of photographs, maps and documents from one of the most important and controversial events in Tulsa’s history as the city prepares to mark the centennial of the massacre in 2021. “We proudly hold one of the most significant collections available on the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, curated by an expert on the subject, librarian Marc Carlson,” Dean of McFarlin Library, Adrian Alexander said. “The collection of emotionally powerful photo images that are at the heart of this historically important archive are available online for all Tulsans and the entire world to see.”

If you don’t know about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, check out this site.

Stories behind the photos

Marc Carlson needed to write a 15-page term paper for a methodologies class, and his wife suggested the Tulsa Race Massacre as a topic. Surprised he had never heard of it, Carlson did what he does best – research. “My paper was 38 pages, and I told the instructor, ‘If you can find anywhere that I’ve been padding, you can give me the F,’” Carlson chuckled.

His paper launched a lifelong investigation into Black Wall Street and the events of May 31 – June 1, 1921, and fortunately for TU, as librarian of special collections and university archives, Carlson began to collect materials documenting the massacre. Now, TU boasts the largest institutional photographic collection of Tulsa Race Massacre archival material, and Carlson owns the largest photographic collection in private hands.

“We have been doing our best to try to make sure the materials are brought together and saved. Because one of the decisions I made early on is that we are the University of Tulsa,” he emphasized. “That’s ALL of Tulsa.”

When Carlson examines the pictures, he doesn’t simply see faces of the past. It’s the untold stories behind the images that inspire his research. “I spend a lot of time trying to identify the photographs and asking questions: Where were they were taken? Who is in them? I try to figure out what the circumstances were behind each photo.”

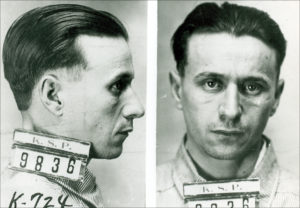

One photo depicts the serious face of a boy striving to be a man. With a cigar dangling from his lips, he is holding a shotgun in front of Greenwood ruins. Carlson believes he is Fred Barker, son of criminal gang leader Ma Barker. “Barker and her family were living in Tulsa at the time. I’m pretty sure they would be all over this event, and it looks just like his mugshot,” he said.

Scribbled writings of witnesses accompany many of the photos, and with each pen stroke, bigotry is engrained. “Dark town’s largest office building,” writes one. Although far more black people were killed, a frontpage headline in the Tulsa World proclaimed, “Two whites dead in race riot.”

The life and legacy of Greenwood

Being born and raised in Tulsa gives Assistant Professor of Anthropology Alicia Odewale a different perspective on the Tulsa Race Massacre. “For a lot of my friends, colleagues and family members, this story is personal,” she said.

Odewale is directing a project on behalf of the 1921-2021 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, titled Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa from 1921-2021. “Through a multi-year project bringing together digital mapping, new archaeology, and the development of a museum exhibit that visualizes the changing footprint of the Greenwood district through time we hope to create new, critical sites of memory for Tulsans to connect to this dark moment in our shared history and consider its legacies and echoes in the present day,” Odewale explained.

Odewale is directing a project on behalf of the 1921-2021 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, titled Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa from 1921-2021. “Through a multi-year project bringing together digital mapping, new archaeology, and the development of a museum exhibit that visualizes the changing footprint of the Greenwood district through time we hope to create new, critical sites of memory for Tulsans to connect to this dark moment in our shared history and consider its legacies and echoes in the present day,” Odewale explained.

For Odewale, the massacre is only a small portion of the Greenwood community narrative. Before Oklahoma was even a state, homes and businesses were popping up in Greenwood. With the excavation, she hopes to share a story of life, not death. “We are focused on finding evidence of livelihood, the remnants of people’s living and working spaces and the people who lost everything while also shining a light on those who survived and rebuilt and continue to do the hard work of revitalizing our community today.”

The excavation is not about discovering items of value. A broken brick is a testimony to the structures of Black Wall Street, or a child’s toy paints a picture of their daily lives. Loss cannot be fully appreciated without first understanding the context.

The excavation is not about discovering items of value. A broken brick is a testimony to the structures of Black Wall Street, or a child’s toy paints a picture of their daily lives. Loss cannot be fully appreciated without first understanding the context.

“As archeologists coming into this space, we are not trying to force any interpretation onto the artifacts. From whatever remains, if we even find anything we can ask questions like ‘What can this fragment of a ceramic plate tell us? It could be anything from status to what kind of market access did black families have at this time to buy new plates.” she explained. “It’s not just about men at work building Greenwood. This is about families who were a part of the legacy of Black Wall Street.”

Discover more about Odewale’s excavation plans.

Community forum

On Friday, February 27 from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m., TU will host the panel discussion “Black Wall Street and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre” to explore the success of Black Wall Street before the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. The forum will cover current diversity initiatives, what Black Wall Street is today and how we can actively engage and support Greenwood businesses.

“It is incredibly special to turn the nation’s lens to this black community once again. It was a beacon of light for black families who were trying to escape the Jim Crow south, searching for a new life, safety, and a promise of prosperity within one of the wealthiest black communities in the country,” Odewale said. “We can now give new honor to that heritage and their descendants by putting together whatever we can find today to share their vital story.”

Explore TU’s special collections exhibition, “Images from the Burning; the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in Special Collections,” and allow the ghosts of Tulsa’s past to serve as a reminder that unfettered hatred and racism leads to devastation. It’s as clear as black and white.