The Program in Law and Public Affairs (LAPA) at Princeton University recently announced its 2020-21 fellows. Among the recipients of this prestigious fellowship is The University of Tulsa College of Law’s Chapman Distinguished Professor of Law Robert Spoo. This LAPA fellowship follows the Guggenheim fellowship he held three years ago.

“On behalf of everyone at TU Law, I congratulate Bob on his well-deserved LAPA fellowship,” said TU Law Dean Lyn Entzeroth. “Bob is not only a wonderful colleague but also an outstanding scholar, teacher and mentor. We will miss him while he is at Princeton, but we wish him a healthy and productive year of research and writing.”

“Robert Spoo is a leader in several different fields,” noted Simon Stern, a professor of law and English at the University of Toronto. “These include literary modernism, copyright, and law and literature. A former editor of the James Joyce Quarterly, he went on to litigate a remarkable, precedent-setting dispute against the Joyce estate. Bob’s work has changed our thinking in all the areas he works on. Being a LAPA fellow will enable Bob to build on his influential research in Without Copyrights: Piracy, Publishing, and the Public Domain (Oxford UP, 2013).”

Lawful pirates and 19th-century U.S. publishing

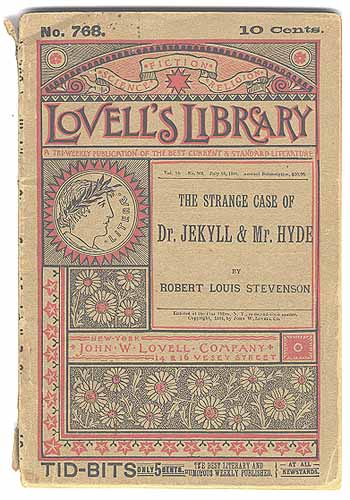

The book to which Stern referred is the first sustained study of a practice in American book publishing called the courtesy of the trade, or trade courtesy. During his LAPA year, Spoo will further explore the courtesy norms that nineteenth-century American publishers fashioned to fill the U.S. copyright vacuum for foreign authors’ works.

These courtesy norms arose because, for much of the nineteenth century, foreign authors did not have copyright protection in the United States. As a result, publishers in this country could reprint and sell the works of non-American authors with complete impunity.

“How maddening it must have been in 1870,” Spoo remarked, “to enjoy copyright protection in one’s own country – Britain, say – but to lack it entirely in the United States with its enormous English-speaking population and high literacy rate. Works by such famous, best-selling authors as Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins were regularly and swiftly annexed by the world’s busiest, hungriest public domain. And nothing could be done about it. American reprinters were immunized as lawful pirates.”

Courtesy among pirates

While formal intellectual property (IP) rights did not exist in the United States for foreign authors, America’s publishing pirates recognized that unregulated competition among themselves would not be a healthy practice for their industry. More profit could be gained by self-regulated coordination.

“The result, emerging in the 1830s and 1840s,” explained Spoo, “was trade courtesy, a process by which publishers agreed to recognize informal property rights in literary texts that enjoyed no formal protections. Thus, if publisher A laid claim to a novel by George Eliot, publisher B would recognize that claim so long as its own association with Walter Scott went unchallenged. Turn-of-the-century publisher Henry Holt, whose extensive archive is held at Princeton, put his finger on it when he observed that trade courtesy was ‘a brief realization of the ideals of philosophical anarchism – self-regulation without law.’”

For his LAPA project, Spoo intends to build on the foundation he laid in Without Copyrights by working on “a thoroughly empirical, archive-based study of American publishers who pioneered trade courtesy to achieve self-regulation and, at the same time, promoted affordable books, literacy and social change.”

But Spoo also intends his study to shed light beyond the publishing industry’s stage. A full understanding of courtesy and lawful piracy offers “valuable, unexpected glimpses into many other facets of nineteenth-century America, such as book manufacturing, the spread of foreign culture through cheap printing, economic protectionism and copyright isolationism in an age of expanding IP internationalism.”

Even more broadly, Spoo situates his upcoming explorations in conversation with other “negative IP spaces” that scholarship has uncovered in recent years. These include domains as diverse as fashion design, stand-up comedy and roller derby. “I hope that my study will also enrich our understanding of private norms and the ways they can be used to regulate ruinous competition and other selfish behavior along the lines that James Acheson has uncovered with lobster-trapping and Robert Ellickson has documented with regard to cattle trespass.”

Are you interested in intellectual property (IP) law past, present and future? TU Law offers first-class training in this diverse and vibrant field. In fact, in August we will welcome a new IP expert to our faculty. Apply to our JD program today to get your career underway.